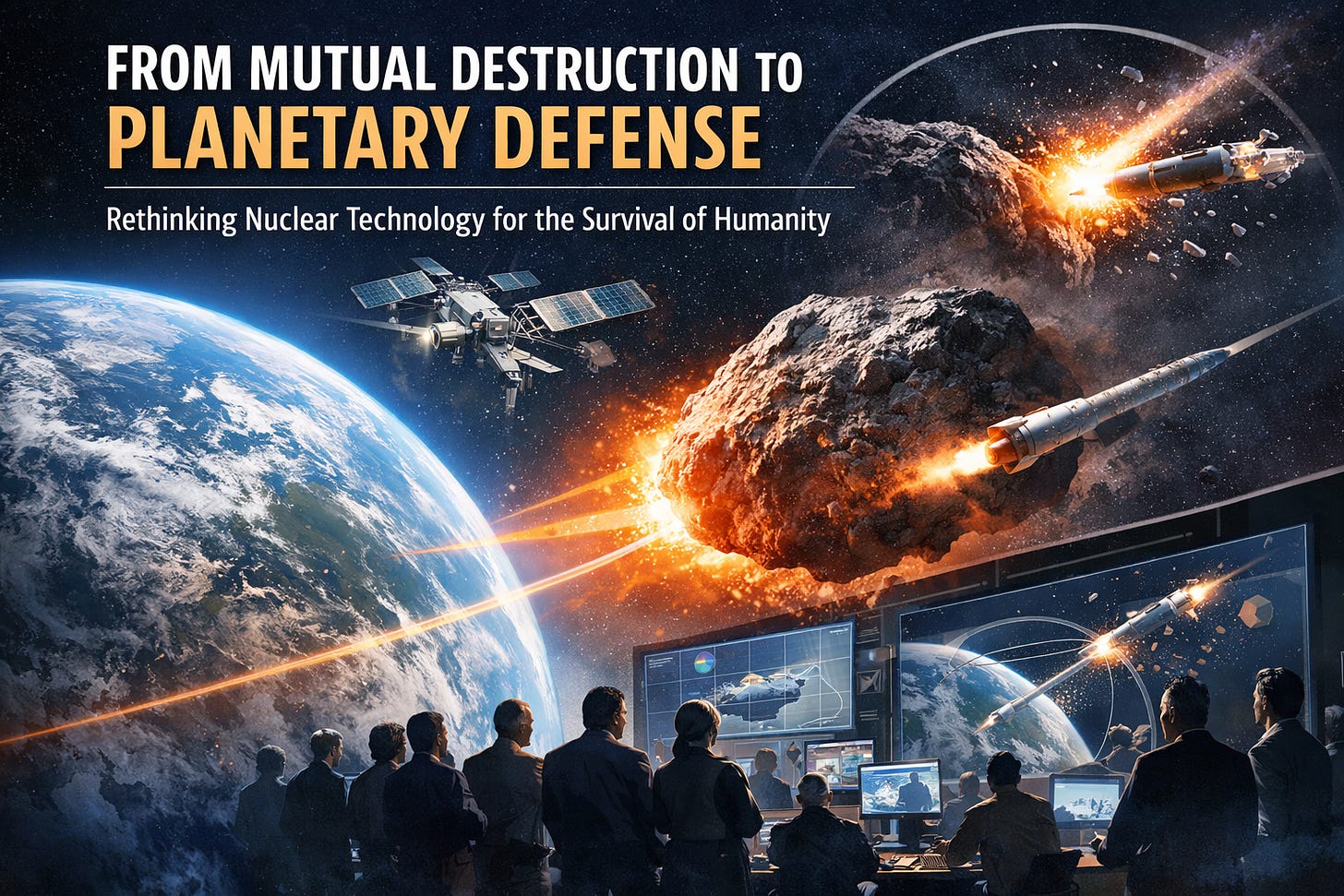

From Mutual Destruction to Planetary Defence

Rethinking Nuclear Technology for the Survival of Humanity

The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs were founded on a sobering realization: humanity had reached a point where its own inventions could erase civilization itself. Guided by the principles of the Russell–Einstein Manifesto, scientists, thinkers, and statesmen came together to prevent nuclear weapons from becoming the final chapter of the human story.

My great-grandfather stood among those who believed that knowledge without wisdom was the greatest danger of all.

I share that belief.

And yet, I also believe we are now confronting a paradox that earlier generations could scarcely imagine.

A Civilization Exposed

In recent public remarks, Neil deGrasse Tyson restated an uncomfortable truth: Earth has no comprehensive planetary defence system. We do not possess a fully funded, globally coordinated mechanism capable of reliably detecting, tracking, and intercepting every potentially dangerous near-Earth object.

This is not about extraterrestrial life or speculative science fiction. It is about asteroids, comets, and cosmic debris—objects whose trajectories are governed by physics alone.

The scientific consensus is clear: within the next 150 to 200 years, the probability of a civilization-ending impact is not zero. Even smaller impacts could destabilize global food systems, economies, and political order. While agencies such as NASA and their international counterparts perform extraordinary work, no single nation has the resources or authority to protect the entire planet.

This is a shared vulnerability—one that transcends ideology, borders, and belief.

The Nuclear Paradox

I support the ideals of nuclear disarmament. No nation should hold the power to exterminate millions—or billions—of lives in minutes. Nuclear weapons represent the darkest expression of human ingenuity.

But here lies the paradox:

The same technologies designed for mutual destruction may also be among the few capable of preventing planetary extinction.

This does not mean endorsing nuclear aggression. It does not mean embracing deterrence theory. It means acknowledging that the technology already exists, and the ethical question is no longer whether it exists, but how it is governed and for what purpose.

Weapons pointed at cities serve fear.

Technologies redirected toward planetary defence serve survival.

A Global Defence, Not a Global Weapon

What is missing is not scientific understanding, but political imagination.

I propose the creation of a permanent, internationally governed planetary defence initiative—under the authority of the United Nations—tasked exclusively with protecting Earth from extraterrestrial threats.

Call it an Earth Defence Force.

Call it a United Earth Nations initiative.

Call it an International Space Defence Agency.

Names matter less than intent.

Such a body would:

Coordinate global detection and tracking of near-Earth objects

Pool scientific, industrial, and computational resources

Develop interception and deflection strategies under strict international oversight

Repurpose existing nuclear and advanced propulsion research for planetary defense only

Remove these capabilities from national militaries and geopolitical competition

This would not weaken peace.

It would redefine peace as the shared commitment to survival.

Humanity at a Threshold

As SpaceX prepares missions to Mars and NASA returns humanity to the Moon, we stand at a historic threshold. Our technological reach is expanding beyond Earth, yet our moral and political frameworks remain bound by tribalism and fear.

We are exquisitely capable of arguing over ideology.

We are dangerously ill-equipped to confront shared extinction risks together.

Asteroids do not recognize borders.

Cosmic impacts do not pause for elections.

Physics does not negotiate.

A Unifying Mission Before It Is Too Late

Every era is defined by the threats it chooses to confront—and the ones it chooses to ignore.

Planetary defence could be the unifying mission humanity has lacked since the dawn of the nuclear age: a cause that demands cooperation rather than domination, foresight rather than reaction, and humility rather than hubris.

The tragic irony of our time would be to destroy ourselves arguing over power while ignoring a threat that cares nothing for it.

We must put our nuclear weapons down—not by denial, but by transformation.

Not by pretending danger has vanished, but by facing a greater danger together.

Instead of pointing instruments of destruction at one another, we should prepare—calmly, ethically, collectively—to defend this solitary blue world we all share.

Because disagreement can be survived.

Division can be healed.

Extinction cannot.

Editor’s Note:

The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs were founded by my great-grandfather (Cyrus S. Eaton) as part of a global effort to confront the moral dangers unleashed by modern science. Working alongside the principles articulated in the Russell–Einstein Manifesto, those early conferences sought to prevent humanity from destroying itself through the use of nuclear weapons.

That legacy shaped how I think about responsibility, power, and restraint.

I remain aligned with the core ethic of Pugwash: that no nation should possess the unchecked ability to annihilate civilization. But I also believe legacy does not mean repetition. It means carrying foundational principles forward into new realities.

This essay reflects that tension.

It does not reject the ideals of disarmament—it wrestles with a modern paradox: that technologies once created for destruction may, under strict international governance, be among the few tools capable of protecting humanity from planetary-scale natural threats.

I offer this piece not as a repudiation of the past, but as an attempt to honour it—by asking how those same commitments to survival, cooperation, and ethical responsibility must evolve in an age of existential risk that extends beyond human conflict itself.